contact@blackcoffeerobotics.com

India, USA

©2026 All Rights Reserved by BlackCoffeeRobotics

Robotic palletization appears deceptively simple on paper: pick boxes, stack them on pallets, repeat. Yet anyone who has attempted to deploy a palletizing system in a real production environment quickly discovers that the gap between "simple in theory" and "reliable in practice" is substantial.

After completing over 50 robotics projects across various industries, we've observed that palletization challenges rarely stem from the robot itself. The real complexity emerges from the interaction between workspace constraints, product variability, system integration requirements, and the need for consistent uptime.

This article examines critical areas where palletization projects typically encounter friction, and how proper engineering analysis during the planning and practices during the execution phase can prevent costly rework.

A common misconception is that if a location falls within a robot's specified reach envelope, motion planning will work. In practice, kinematic feasibility is only the starting point. A robot palletization system might technically reach a position but lack sufficient joint range to approach from the required angle, or it might reach the position but be unable to maintain the straight-line trajectory necessary for stable box placement.

Conveyor heights, pick zone locations, and pallet staging positions must all be optimized not just for individual reachability, but for motion efficiency across the entire operational envelope. A poorly positioned conveyor might force the robot into awkward configurations that add seconds to every cycle, reducing throughput by 20-30% compared to an optimized layout.

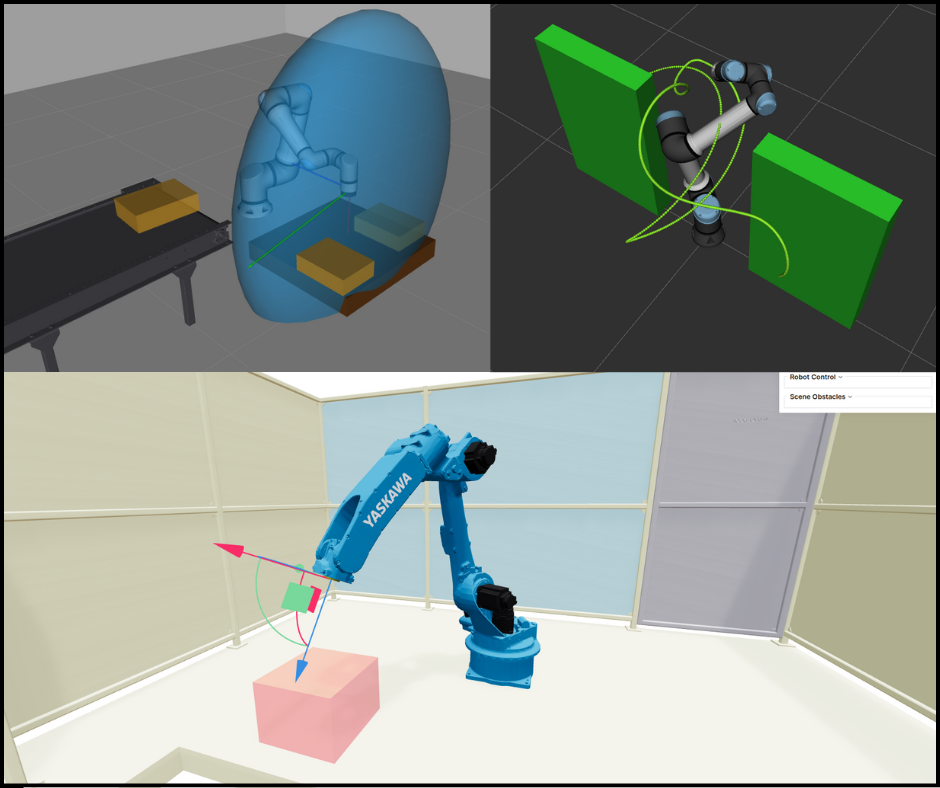

We have seen and tackled reachability issues in multiple robotic applications. We address these constraints through computational workspace analysis during the design phase. Rather than relying on vendor datasheets or intuition, with our in-house tools, we simulate thousands of potential configurations across different robot models, evaluating not just reachability but motion efficiency, collision likelihood, and cycle time impact. This analysis is vendor-agnostic; we can evaluate solutions from FANUC, Hyundai, Universal Robots, or any other platform like Robotiq palletizer, allowing equipment selection to be driven by actual performance data rather than existing vendor relationships.

The choice between vacuum grippers and mechanical clamps isn't just about holding force; it's about how that choice cascades through robot selection, cycle time, and ultimately system economics.

Vacuum systems offer flexibility across varying box sizes and surface finishes, but they introduce dependencies on compressed air quality and surface cleanliness.

Mechanical clamps provide more deterministic grasping but require precise box positioning and may not accommodate significant dimensional variation.

The decision becomes more complex when considering multi-pick capabilities: gripping two boxes simultaneously can theoretically double throughput, but it also doubles the payload. It may require a larger robot with different kinematic characteristics.

A collaborative robot rated for a 20kg payload might handle single-box palletising adequately, but adding a dual-pick gripper could push it beyond safe operating limits or slow joint velocities enough to eliminate any throughput gain. Conversely, oversizing to an industrial robot for future dual-pick capability might introduce unnecessary cost and footprint for the current application.

Proper selection requires dynamic simulation of the complete pick-place cycle, not just payload calculations. Joint velocities, accelerations, and trajectory planning behaviour all contribute to actual cycle time. We've seen cases where a lower-payload robot with optimised kinematics outperformed a higher-payload alternative simply due to better joint configuration for the specific workspace geometry. Each workstation is unique, and equipment selection should reflect actual operational requirements rather than general rules of thumb.

Production environments rarely involve a single conveyor feeding a single pallet. Real deployments often require managing multiple input streams, different product lines converging on the same palletizing cell, or multiple pallets being built simultaneously to match order composition.

The integration challenge isn't just mechanical. The system must coordinate:

A poorly designed integration can leave the robot sitting idle between motions, or in dual-robot scenarios, force the robots to work sequentially rather than operating in parallel through coordinated workspace sharing.

Vision-less palletization systems, which rely on mechanical guides and assumed box positions, can achieve impressive cycle times in controlled conditions. Their limitation isn't speed; it's brittleness. Without perception feedback, these systems cannot detect when something goes wrong until the error compounds into a more serious failure.

A slightly misaligned box might be placed successfully once, but subsequent boxes stacked on that foundation inherit the error. By layer three or four, the entire pallet may be unstable, requiring manual intervention. Meanwhile, the robot continues operating normally because it has no way to detect the problem.

Vision-guided systems introduce their own challenges:

A poorly implemented vision system might be slower than a blind system without providing meaningful error detection.

Having worked with various camera systems and vision algorithms across both indoor and outdoor scenarios, we design integration solutions specific to each facility's needs

We give equal importance to the human machine interface: when the system detects an anomaly, operators need clear information about what happened and what intervention is required.

Single-SKU palletization with fixed patterns is a well-understood problem. When every box is identical and arrives in a predictable sequence, pattern generation can happen offline, and the robot executes a predetermined choreography. If you are considering a Mixed-SKU palletization for your facility, this model will break entirely.

When box dimensions vary within a single pallet, placement becomes a real-time optimization problem. The system must decide where each box should go based on:

This requires runtime pattern generation, treating placement as a continuous decision problem rather than a fixed sequence.

Academic research on bin packing optimizes for density. Industrial palletization must balance density against cycle time, stability, and motion planning feasibility. A mathematically optimal packing might require approach angles the robot cannot achieve, or might create overhangs that violate stability constraints. The pattern generator must understand not just geometry, but the capabilities and limitations of the physical system.

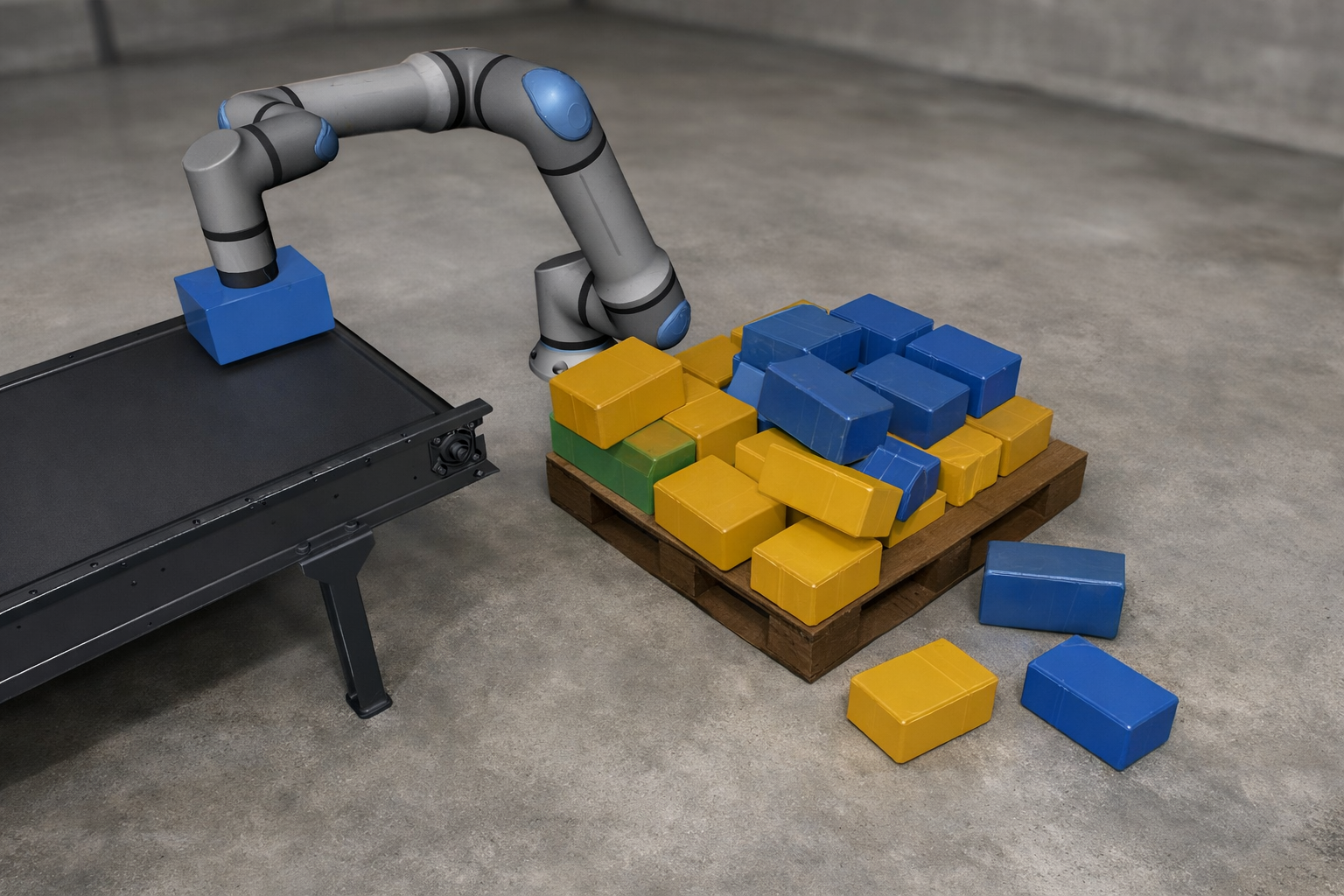

Here is a demonstration of a mixed-SKU palletization system that handles different SKUs with box dimensions varying by factors of two or more, without requiring manual reconfiguration between product changes.

If you're evaluating automated palletizing, we welcome a conversation about your specific requirements. Sometimes the right answer is off-the-shelf equipment with thoughtful integration. Sometimes it requires custom analysis to avoid costly mistakes. Either way, the implementation should start with understanding your operational constraints, not with a product catalogue.

We're available to discuss workspace analysis, vision-guided palletizing, or whether your application might benefit from advanced mixed-SKU capabilities. Reach out if you'd like to explore what's possible for your facility.

.webp)